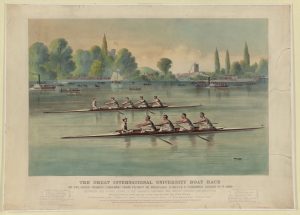

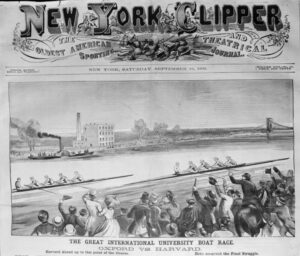

The Great International Boat Race

Bill Miller

(click on images to enlarge)

In 1869 Harvard challenged Oxford to race on the Oxford-Cambridge (Putney to Mortlake) Boat Race course outside London. The public interest was huge with more publicity than any sporting event to date. The new Atlantic cable allowed daily reports to be received by all major newspapers across America. The race was closely fought and both crews were admired for their sporting spirit. The result in America was an explosion of interest in collegiate and amateur rowing.

Background

Bill Miller Collection

To really understand the impact of Harvard-Oxford boat race, we need to get a glimpse of rowing in the mid-19th Century. Rowing permeated many parts of the commercial world in America during the early part of the century. From fishermen rowing dories to the New York City Whitehallers rowing fares across rivers, thousands of people earned a living from rowing. From this broad exposure to rowing, many more thousands of people were interested in watching rowing races, with many wagering on the outcome. This produced a whole industry of professional rowing for financial gain. There were the scullers and rowers themselves, the backers or financial syndicates, the gamblers and sharpies trying to make a quick buck, hotel keepers, even railroads managers, all vying for profit.

The scullers and rowers were local, regional and national heroes. Thousands of spectators would turn out for a match with thousands of dollars bet on the outcome. Most all the public’s attention through the first two-thirds of the century centered on professional rowing. (see The Wild And Crazy Professionals)

Amateur rowing existed but didn’t have a strong following and the only colleges that were racing were Harvard, Yale and Brown.

The Challenge

In 1867 there was a noteworthy event at the Paris Exposition in France. One of the events was a rowing contest in four-oared shells on the Seine. Seven boats competed; three from France, one from Germany, two from England, and one from Saint Johns New Brunswick. The New Brunswick crew won and returned to Canada as national heroes. The Canadian crew were World Champions and would forever be known as the Paris Four. Of the two English crews, one was from the London Rowing Club (2nd) and the other from Oxford University (3rd).

There was another North American crew contemplating attending the Exposition but had to pass because they had difficulty assembling a crew. This American crew was the Harvard University Boat Club.

On November 6, 1867 R.C. Watson sent a letter of challenge to Oxford for an eight-oared race: 1. on a straight course, 2. without coxswains, 3. between the 1st and middle of September. Oxford raced exclusively with coxswains while Harvard raced in fours and sixes without coxswains. The coxswain’s issue couldn’t be resolved, so they never reached an agreement. However, the idea was planted and resulted in “The Great International Boat Race” of 1869.

To the President of the Oxford University Boat Club,

The undersigned, in behalf of the Harvard University Boat Club, hereby challenges the Oxford University Boat Club to row a race in outrigger boats from Putney to Mortlake, some time between the middle of August and the 1st of September, 1869, each boat to carry four rowers and a coxswain. The exact time to be agreed upon at a meeting of the crews. This challenge to remain open for acceptance one week after date of reception.

In 1869 all the pieces for an international race came together, but not smoothly. It seems in April that Harvard Captain, William Simmons, sent a letter of challenge to both Oxford and Cambridge Universities but Harvard University faculty questioned Simmons whether he had the approval to do so. A race overseas would conflict with the scheduled Harvard–Yale race. After some debate, the faculty determined that this was a private challenge sent by Mr. Simmons and not a University academic matter. Meanwhile, Cambridge showed little enthusiasm, delayed responding for months and then said they wouldn’t be able to organize a crew. At Oxford James Tinne, Captain of OUBC, called a meeting of the 21 captains of the college boat clubs to vote on accepting or rejecting Harvard’s challenge.

J.C. Tinne recalls:

When the challenge came from Harvard, it was necessary for me to call a meeting, to ask consent of the O.U.B.C. to accept the challenge, because there was a lex non scripta that the O.U.B.C. was formed only to row against Cambridge. The voting resulted in 10 AYES, 10 NOES. It was then noticed that no representative of Oriel College was present, so we sent for one, and the voting resulted in 11 AYES, 10 NOES. Next day a newspaper reported that the challenge was accepted unanimously!

In May, Simmons received notice that Oxford accepted.

Bill Miller Collection

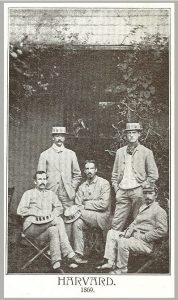

The Harvard Crew:

1 – Joseph S. Fay (replaced George Bass)

2 – Francis O. Lyman ‘71 (replaced Sylvester Rice ‘71)

3 – William H. Simmons ‘69

4 – Alden P. Loring ‘69

C – Arthur Burnham

Original crew (l>r): George Bass, Arthur Burnham, William Simmons, Sylvester Rice, Alden Loring

Bill Miller Collection

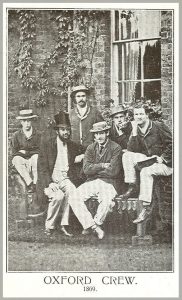

The Oxford Crew:

1 – Frank Willan *

2 – Alfred C. Yarborough

3 – James C. Tinne *

4 – Samuel D. Darbishire

C – Francis H. Hall

* raced at Paris Exposition-1867

It’s very interesting because Harvard had one of its best squads of all time. They actually sent a six-oared crew to Worcester to race Yale without some of their best men who would be arriving in England at the time of the Yale race. Yale was shocked when Harvard defeated them with what was essentially their second crew.

Alden Loring, stroke of the ’69 Four, was the most successful oarsman at Harvard. As a freshman in 1866 he rowed #2 in the University Race that defeated Yale. He stroked the winning Harvard six in 1867 and 1868, thus successfully defeating Yale in the “University Race” in his first three years at Harvard. Now, in 1869, he was stroke-oar of the Four while his teammates were defending at Worcester.

Meanwhile, Oxford had their best squad to date. Frank Willan rowed in the winning Oxford boat in 1866 and became OUBC President for 1867. James Tinne joined the crew and Oxford won again. Also in 1867 Willan and Tinne rowed in the Oxford Four that placed 3rd in Paris. In 1868 Willan repeated as President and Darbishire and Yarborough joined Tinne for another victory over Cambridge. In 1869 Tinne was elected OUBC President and again with Willan, Darbishire and Yarborough defeated Cambridge.

Tinne was 6’3″ and 189 lb. by far the largest oarsman of the day. They were, man for man, bigger and stronger than Harvard averaging 15 pounds heavier per man. It was an awesome crew. In the book The University Boat Race – G.C. Drinkwater and T.R.B. Saunders state “They were said at that time to have been the best four that ever rowed”.

Preparation

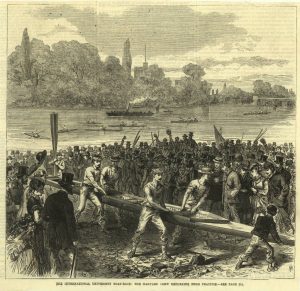

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News,

Bill Miller Collection

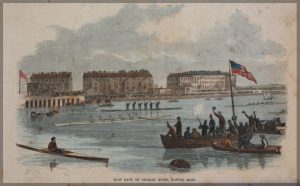

At Harvard planning began for their race in England. The crew consisted of William H. Simmons ‘69, Alden P. Loring ‘69, George Bass, Sylvester Rice ‘71 and Arthur Burnham as coxswain. Their first race was unsuccessful against a very good Boston professional crew, but later at the July 4th Regatta in Boston they won defeating all the best four-oars in America.

Harvard’s sendoff was impressive. They took the train to New York; were guests of the Nassau Boat Club; were toasted at banquets; and were cheered by the citizens of New York City at their departure on the City of Paris on July 10th. They left behind the six oarsmen to contest Yale on July 23. The Harvard party consisted of the four oarsmen with their coxswain, a manager–Mr. William Blaikie H’66, their Cambridge cook–Mr. E. Brown, attendant–George, boatbuilder–Mr. Charles Elliot of Greenpoint, NY and other supporters. Elliot brought a brand new shell along with the one he previously built for them and the pieces of yet another ready to be constructed should either of the two prove to be undesirable.

From Harper’s Monthly, December 1869:

After a most enjoyable trip, with very little seasickness, obliging officers, and a short run, they reached Liverpool on July 20th, where they were met by representatives of the Liverpool and Chester clubs, inviting them to put in at least a day with them. They got forward at once to Putney, the most thorough arrangements having been made by Stanton Blake, Esquire of New York City for their conveyance over the London and Northwestern and Southwestern railways, free of any expense, special cars and engine placed at their service.

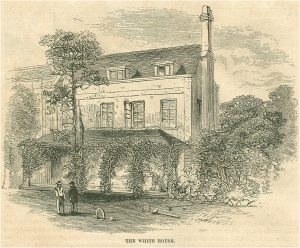

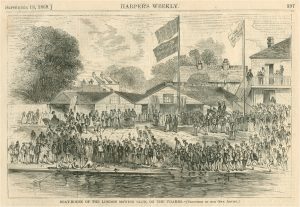

In London “a most suitable and comfortable dwelling was secured called the White House. With an acre of garden and a high wall about it and the river being within 20 feet of the garden gate, and the boathouses not a stone’s throw off”. The London Rowing Club gave full use of all their facilities and equipment.

Harper’s Monthly,

Bill Miller Collection

As it turns out, Bass and Rice became ill soon after arriving in England, so Joseph Fay and Francis Lyman from the Harvard six sailed immediately after the Yale race. They arrived in England on August 9th.

Training commenced. They became unsettled with their shells. Their Boston shell was 52 feet-6 inches long, which is very long and thin compared to the 40 footers we use today. The new shell built by Elliot just before departure was 49 feet long. This boat sagged when they rowed it and was difficult to steer on the twisting Thames course. Four English builders: Salter, Jewitt, Clasper and Searle offered new shells free of expense. Elliot took the pieces and plans for a new boat that he brought along in a chest, “hired two young fellows to help him, working 13 hours a day himself, he succeeded, five days before the race, in turning out his new boat” (Harper’s). The new Elliot, a 44 foot shell, met their approval and the equipment issues were settled just in time. Most all English descriptions praise the new American boat as the finest they’d ever seen. J.C. Tinne recalls, “Harvard had an A1 boat.”

Ironically, Oxford had two shabby boats to choose from. Tinne again, “We had eventually to take the less bad of the two boats – [it] did not travel between the strokes.”

Illustrated London News

However, Harvard had other concerns. Again from Harper’s:

As the course to be rowed – the best known rowing track in the world, from Putney to Mortlake, on the Thames – was only four miles out of London, and as all the papers agreed that the number of spectators would be unprecedentedly great, the danger of obstruction to the contestants plainly demanded much attention.

In fact, the two chief dangers that seemed to threaten our men from outside sources were, tampering with what they ate or drank before, and interference in the race itself. The former was guarded against with great care for ten days beforehand, by having a double allowance of food and drink coming into the house, one through the regular channels, the other by secret means and [by] the hands of Harvard men only. The men with whom we were to row, or their friends, we never thought of mistrusting. It was only the tools of betting men whom we had to fear.

Anticipation

To say that there was keen interest in the race would be a considerable understatement.

From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 19, 1869:

Nothing is excited so much interest among the collegians of the country at the present time as the boat-race which is to take place in English waters between a select four of the Oxford University crew and the Harvard College crew of four, with coxswains added. The collegians of the British Isles are even more alive to the matter than ours, and the coming of the Harvard crew and their friends is looked forward to with anticipations of an exciting contest. Thousands and tens of thousands of people will witness the race from the banks of the Thames, and the attention of the hosts of men on both sides of the Atlantic will be fixed on the eight youths who are to struggle for supremacy.

From The H Book of Harvard Athletics:

The New York City Hall had been decorated with flags in anticipation of victory, and they had prepared to fire one hundred guns to celebrate the defeat of England. Harvard for once was the great popular American University, representing the entire country, and her crew was looked upon with enthusiasm…

From Aquatic Monthly, July 1872:

In the city of Milwaukee preparations were instituted for a grand pow-wow in case the American crew should be victorious. A public meeting was called at the City Hall, a salute of fifty guns was to be fired, and the ringing of bells and blazing of bonfires, were to add their effects to the general rejoicing.

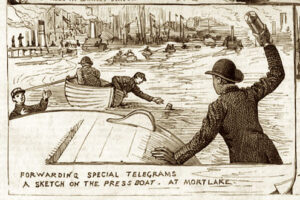

Fifteen American correspondents were on hand to pen their reports to be tapped over the new cable laid across the Atlantic.

Race Day

Race Officials:

Referee – Thomas Hughes (novelist, founder Cornell crew)

Oxford Umpire – J. Chitty (Oxford oarsman)

Harvard Umpire – F.S. Gulston (Captain, London Rowing Club)

Starter – William Blaikie (Harvard oarsman)

Finish Judge – Sir Aubrey Paul

Press steamer – “Sunflower”

Officials’ steamer – “Britannic”

Boats:

Harvard – new boat by Charles Elliott. Greenpoint, NY (built at Putney)

Oxford – new boat built by Jewell, Dunstan

Race Time:

5:00 PM – August 27, 1869

Again, Harpers Monthly:

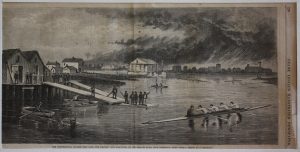

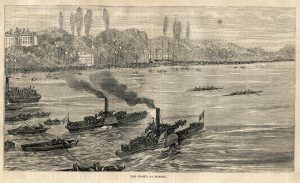

At three the Thames Conservancy Board locked up the river, and even as early 4:00 the track was about clear. All day long Putney had been very lively; and the booths and every other apparatus that has yet been devised for the spasmodic gathering of small change, which had established themselves along the bank, made every one full of spirits in anticipation. One long, steady, uninterrupted stream of boats of every dimension and cut, from the frail ten-inch single-scull shell to the lumbering lighter, as large as the craft that first carried Columbus to the New World, flowed onward up the river, under the Putney Bridge, and through the Aqueduct, to their chosen spots on either bank. The London rabble could not all have been on the banks, because so many were on the water. The barges already referred to suddenly became, instead of unsightly old hulks they are, perfect bouquets of beauty, from gaily-decked loads they bore.

Illustrated London News, Bill Miller Collection

From the stations near Putney, by all the roads and foot-paths, long lines of eager people poured down toward the river. Great ‘busses’ with three horses abreast, and the ordinary kind of two, with ‘ten inside and fourteen out,’ and a burly, dignified, weather beaten, grandfatherly-looking old whip perched a little higher than any one else, who stopped about once in fifteen minutes for his grog or his ‘arf a pint of h’olden bitters,’ and nodded complacently to the demure little bar-maid who brought it; lumbering dog-carts with four and six on board, and perhaps a pony hardly larger than a well-grown Newfoundland to pull them; stately four-in-hands, with their jaunty little outriders and liveried footmen – all flowed on in solid lines toward the little river which has been famous for thousands of years.

Arrangements were made by the Chief of Police, Colonel Henderson, for keeping the crowd orderly that were simply unprecedented. Six years ago forty constables were deemed sufficient to keep in order those who then attended the Oxford and Cambridge Varsity race. On the 27th of last August eight hundred police officers were detailed to watch the people on the bank alone, while the river police boats were placed at every necessary point. Ropes were extended early in the afternoon across all roads leading to the river-edge, so that none except those on foot could reach it.

A little before five o’clock a procession of men, nearly all Americans, thirty strong, filed out through the garden gate of the White House and went directly on board the umpires’ boat. Among them might be seen Russell Sturgis of the house of Baring Brothers, a Harvard graduate of 1823; J.S. Morgan, the successor of George Peabody; Mr. Moran, Secretary of the English Legation; Professor Asa Gray, the botanist; Thomas Hughes [English novelist & founded Cornell crew in 1870], Charles Reade, George Wilkes, of New York, and many younger men, well fitted to represent the Americans. The thirty Oxford men they found on board were mostly all former Varsity oars, and most keenly did they watch every thing that was going on.

Harper’s Weekly,

Bill Miller Collection

A little bustle at the London Rowing Club house, and the crowd separating, announce the launching of the Oxford boat. She is soon manned and away, greeted warmly all along the bank. Shortly after the Harvard men put out, and they too get their share of the applause. Both paddle over to the umpires’ boat. The toss for place had been made by the referee, and won by Harvard. She chose the Middlesex station, for the reason that, for the first half mile, this position would give her the pole. They back up to the line: two stout boats are attached to it at perhaps twenty yards apart. In one is a Thames waterman, in the other Walter Brown [American professional sculler]. The former catches the sternpost of the English boat, the latter of the American. Both wheel into line. The crowd on shore is perfectly quiet.

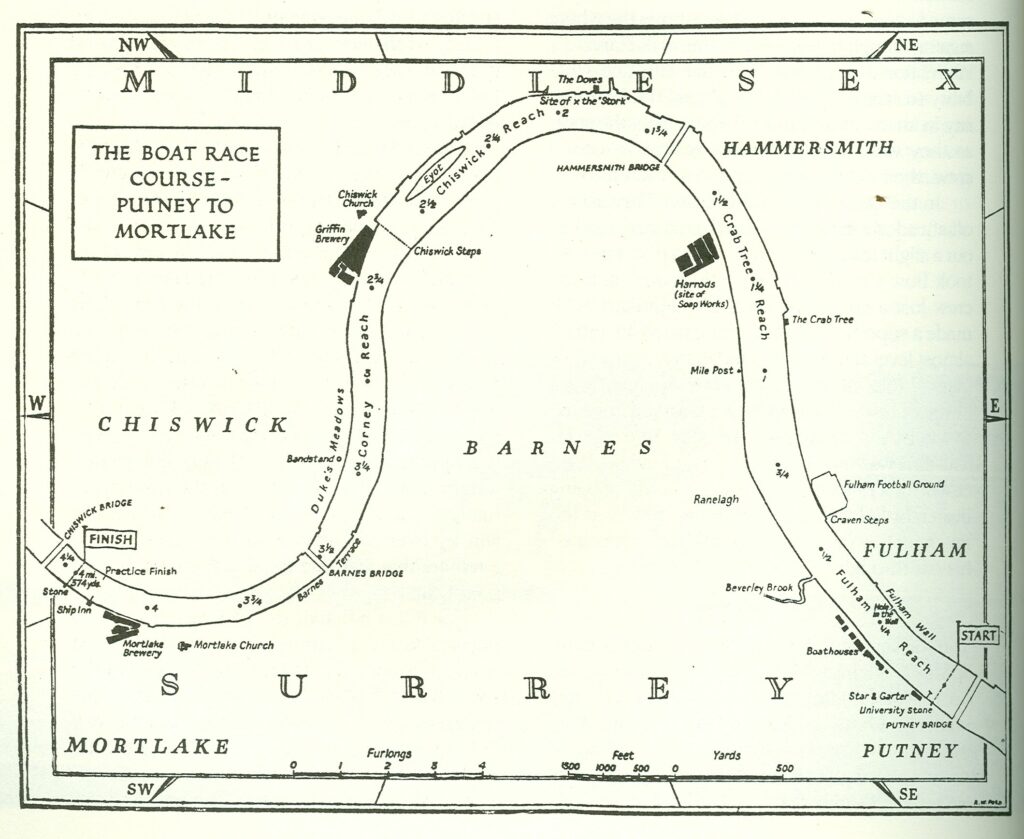

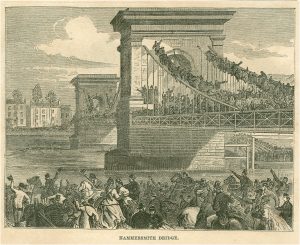

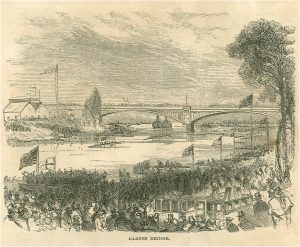

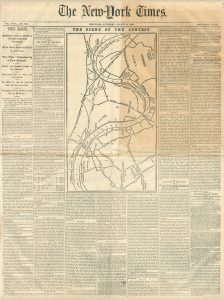

The racecourse is 4-1/4 miles with variable currents starting at Putney, lower right. The course passes under the Hammersmith Bridge about 1-3/4 miles into the race. Then a sweeping turn to port and down the Corney Reach to Barnes Bridge, 5/8 mi. from the finish line at Mortlake, lower left.

Harvard on the Middlesex station gave her an advantage in the first 1-1/2 miles, but then the huge turn to port would give Oxford in the Surrey lane the advantage if she could prevent Harvard from obtaining open water.

Alden Loring described their clothing many years later in the Boston Sunday Herald, Feb. 20, 1898:

The Oxford Crew appeared at the line in their regulation navy uniforms with blue sweaters and straw hats, which they took off just before the start, rowing in white sleeveless shirts and bareheaded. The Harvard oarsmen were nude above the waist and had crimson handkerchiefs tied about their heads.

Back to Harper’s:

The starter [William Blaikie H’66] cries out, “I shall start you by the words, ’Are you ready?’ Then there will be a pause for a moment, and repeat, ‘Are you ready?’ If no response comes, I shall say, ‘Go!’ If either side breaks an oar in the first dozen strokes, I shall call you back by swinging my hat backward vigorously. Now, then, look out! ‘Are you ready?’” “No!” says Mr. Tinne. “Again: Are you ready?” “No!” again from the same gentleman. “When will you be?” “Directly” [replied Tinne]. Their boat was not headed just right, and they were swinging it into place. “Are you ready? Are you Ready? Go!” And 15 minutes past five o’clock, [actually, fourteen minutes – 6 ½ seconds to be precise] both boats sprang away very fairly together.

Harper’s Monthly,

Bill Miller Collection

Oxford rowed one more stroke that minute than she had ever shown in her hardest spurt in practice, scoring just forty-two. Loring, in our boat, was setting them fort-six. The papers would allow Harvard to get, perhaps, quarter length ahead in the first mile, but never more; nor would she hold that long. But somehow she was slipping along at great speed; and when another minute had gone, and Oxford had pulled forty more, and Harvard forty-two, the latter was a fair half length in advance.

Hardly had the first stroke been taken when the mighty army on shore poured out the feeling which had been all this time pent up, in one tremendous roar. Preconcerted though it was, the wild “’Rah! ‘Rah! ‘Rah!” of the little knot of partisans on the umpires’ steamer hardly reached Loring’s ear first. Burnham [Harvard’s coxswain] now takes his men out toward the others a little, and, for a moment, a foul seems inevitable. “Look out, Mr. Burnham!” shrieks the little dark-blue [Oxford’s] coxswain; and the former pulls his starboard rudder-line and makes for mid-river.

Another minute is over, and now the strokes are thirty-nine and forty – the latter by the Americans. And the half length has become a whole one. And such a din! Why, those on the umpires’ boat, not eighty feet from the racers, almost tore their throats in efforts to be heard by their favorites. And yet the latter said afterward that they did not hear them once. “That’s it Loring! Let ‘em have it! Let ‘em have it!” “Oxford! Oxford! Oxford!” “Burnham, what are you about?” And, sure enough, what is he? For he is clearly a length and a half to the fore, and yet he does not cross over to what would have been a shorter track, and take his rival’s water.

Here was the fatal mistake that day. So said every fair-minded man, English and American, on that umpires’ boat. He makes a wide sweep toward the Middlesex shore and the Crabtree Inn, and reaches Hammersmith Bridge in eight minutes twenty-one seconds – very good time, and still a whole length in front.

Harvard leading

Bill Miller Collection

Harper’s Monthly,

Bill Miller Collection

Oxford’s stroke had fallen to thirty-seven, Harvard’s to thirty-nine. Now Loring puts on the steam and draws away again, but it does not last. The strongest man in the Harvard boat – the strongest man in either boat – gives out now first. For some days past he had been slightly unwell, but, confident in his strength, he believed he would be up to his work. Foot by foot, inch by inch, the slow, ponderous swing of the dark-blue creeps up on her more active opponent. An eddy right off Chiswick Ait, into which our men are steered, delays them so that the two boats are level.

Down to it again lay the men of the crimson colors, and fight madly every inch of the way. But now their stroke [man] seems to slacken, and looks distressed, and in the next minute the coxswain is vigorously dashing water on his after-men – a novel but excellent expedient. All the way, since they drew level, Oxford has been steadily pulling forty strokes a minute, while her antagonist never does over thirty-nine.

Harper’s Monthly,

Bill Miller Collection

At Barnes Bridge, five furlongs [5/8 mile] from the finish, two lengths of clear water separate them [Oxford leading]. For miles back the dense mass on shore has been swaying and struggling, and now, like a mighty river, is sweeping on over fields and fences, ditches and hedges, wild, mad with fierce excitement, yelling at every breath, and with all its might. Seven hundred and fifty thousand people are said to have been there that day. Never but once in this generation has such a crowd been seen in England, and then when the Prince of Wales first brought his wife home. The Derby Day can not compare.

And now they approach the goal. Most admirably has the track been kept clear, until now a boat, containing a lady and gentleman, stumbles into the course, and for a moment threatens to impede the leaders. Spurt after spurt do the losing men give their frail little craft, and when the winner crosses the line but “half to three-quarters of a length clear” separates them; so says Sir Aubrey Paul, the judge at the finish.

Illustrated London News,

Bill Miller Collection

Note: Oxford had actually opened about three lengths clear near the finish when the spectator craft caused the English crew to slow to avoid them and then they rowed the last few strokes easily to reach finish line. This allowed Harvard to close the margin to the reported “half to three-quarters clear”.

Harper’s:

Both crews turn about and prepare to go down the river. Oxford starts away and paddles slowly down. Harvard delays a few minutes, until the small boats swarming around cover the river so completely that one might almost walk across. Though the crowd press so closely, not only is no unkind word heard, but “Bravo, Harvard! Bravo! Well rowed! Well rowed!” is rung in their ears. The press becoming so great that it is useless to attempt to proceed, the men disembark, and, after remaining a short time on their little steamer, come on board the umpires’ boat. Tired and hot they looked, and no true man could look otherwise after such a race. They steam away down the river and get quietly home.

Illustrated London News

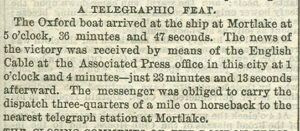

One enterprising American reporter wrote a mid-race section of his report, then folded it into a wood canister, tossed it to a waiting currier who rushed it off to the telegraph office. His American newspaper could start setting the type almost before the race ended.

Rowing historian “Thomas Mendenhall wrote, “The first English press ‘extra’ after the race, sold a second 25,000 copies within forty-five minutes.”

Bill Miller Collection

A while ago there was a TV documentary about boxing. A historian that was interviewed described the 100,000 spectators and the huge press the match received. He said, the next day nearly half of the front page of the NY Times was dedicated to the reporting. Well, on August 28, 1869, over 80% of the front page of the NY Times was dedicated to reporting about the Harvard-Oxford Boat Race.

Aftermath

The huge public interest in the Harvard-Oxford Boat Race had an unbelievable affect on rowing in America.

George Balch states in the great book he wrote, The Annual Illustrated Catalogue and Oarsman’s Manual For 1871:

The newly awakened interest in rowing at many of the most noted seats of learning in the country, where heretofore little, if any, attention has been paid to this branch of athletic exercise, will undoubtedly lead, in time, to a great increase in the number of candidates for aquatic honors at future annual regattas, and bring to notice undergraduate crews, which may yet rival the performances of their predecessors.

Here are a few facts:

Within 24 months after 1869 there were 138 new boat clubs, that we know of, founded in America, .

In 1869 only Harvard, Yale and Brown raced. Then soon after, rowing programs were formed at many colleges: 1870-Cornell, Princeton, Columbia College, St. John’s College-Annapolis, Mass. Agricultural College, Amherst College, US Military Academy, Ohio Wesleyan, Griswold College-Iowa, Lafayette College, and in 1871-Bowdoin College. The 1874 Saratoga Regatta also included: Wesleyan, Dartmouth, Williams, Trinity, and Rutgers.

Before 1869 collegiate rowing was a novelty and within two years it was a fully developed collegiate sport, the first organized collegiate sport. In 1871 the Rowing Association of American Colleges was formed and conducted the first college championship and set rules of eligibility that became the foundation for the NCAA.

In 1872 the National Association of Amateur Oarsmen (NAAO) was founded, the first American national association for any sport with the first American rules defining an amateur.

Conclusion

Prior to 1869 most all interest was in professional racing. The Harvard-Oxford Boat Race ignited huge interest in collegiate and amateur rowing. By 1896 the Olympic Games were established, collegiate rowing captured the public’s attention, and professional rowing was dead.

The Great International Boat Race, although not in America, was the greatest American rowing event in the 19th Century.

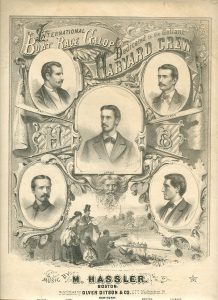

Thomas E Weil Collection

Sheet music was composed and printed to capitalize on the popularity of the race.

Books/Periodicals referenced

- The University Boat Race, Official Centenary History – G.C. Drinkwater/T.R.B. Sanders, 1929

- International Training-1869 – J.C. Tinne, 1923

- The Annual Illustrated Catalogue and Oarsman’s Manual – G. T. Balch, 1871

- H Book of Harvard Athletics – J.A. Blanchard ed., 1923

- The Harvard-Yale Boat Race 1852-1924 – T.C. Mendenhall, 1993

- Harper’s Monthly – #235 December, 1869 The University Rowing Match

- Aquatic Monthly – July, 1872

- Boston Sunday Herald – Feb. 20, 1898

- New York Times – Aug. 27, 1869

- Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper – June 19, 1869