The Development of Rowing Equipment

Bill Miller

Illustrated London News

This page contains information about the development of rowing equipment beginning about the end of the 18th century. Many of us sit back and think that most of the significant improvements in rowing equipment were made in the 20th century. When reviewing all the developments, patents, etc, it’s clear that huge progress was made in the mid-19th century. In 1825 oarsmen were competing in clinker built, in-rigged boats. By 1875 they were competing in sleek, lightweight, out-rigged, sliding seat “shells”, very similar to today’s high performance boats.

In 1868, Waters, Balch & Company of Troy, NY manufactured paper boats. This was a process of layering sheets of paper (fibers) and impregnating them with a varnish/shellac type material, almost like a plastic material. Today’s boats use carbon fibers and epoxy (fiber reinforced plastics – FRP); a very similar process. The dimensions and weights of the shells were very close to today’s specs.

The roots of our sport go back to the early industries of the 17th/18th centuries and earlier. On the River Thames in London, the river was used to transport goods and services. One service in particular flourished with thousands employed. The livery service transported people from one side of the river to the other and from the lower portions to the upper portions of the city. These watermen were closely governed by Parliament and had to spend years as an apprentice.

It was very early on when one waterman decided to challenge another waterman or when one passenger urged his waterman on to a speedy passage, that boat speed became an asset. A waterman could enhance his income by receiving a gratuity from his pleased patron or gain publicity and a reputation by winning contests. Racing between watermen soon flourished.

In 1715 an actor named Thomas Doggett used these watermen regularly to cross the Thames to get to his theatre appearances. He decided to place a sum of money in an endowment to provide for a race for a Coat and Badge to take place “forever” for 6 emerging watermen. This competition continues today.

In the United States, much the same was done, especially in New York City, where people were transported across the rivers by livery boats. The steps at the end of Whitehall Street became the Grand Central of the water transport era. Soon races were contracted with rather large purses. The boats, known as Whitehalls were durably built, in-rigged wherries.

Another line contributing to rowing competition descends from the naval and merchant shipping trade. Naval cutters, pilot gigs, ship’s tenders and the like were used regularly to transport people to and from the larger ships. As soon as you get two or more rowing craft going in the same direction, a race will develop. These challenges were often made in a harbor between two visiting ships or a visiting ship and a local crew. Sums of money were wagered and a purse of money was waiting for the winning crew.

Boats and Hardware

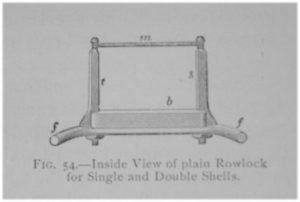

As the seriousness of the racing and the size of the prizes grew, oarsmen looked to improve their equipment to give them an edge. In 1828 Anthony Brown, England, attached crude wooden out-riggers to a boat. The out-rigger allowed for a narrower, speedier boat to be built without the need to support an oar directly sitting on the gunwale (in-rigged). Frank Emmet, of Dent’s Hole on the Tyne, had a try and in 1830 produced the “Eagle” with iron out-riggers. The metal out-rigger was perfected by Harry Clasper, Newcastle, England, c. 1841, and his claim of “Inventor of the Outrigger” has withstood the test of time. The in-rigged and out-rigged boats of this era had a fixed seat, moveable foot-board, thowle rowlock, and an exterior keel.

Shell Construction, c. 1840s

The next major development was the smooth skin, keel-less hull. The boat became known as the “shell” because its structure was internal and a smooth delicate egg shell like skin was formed around it. According to U.S. boat-builder, George Pocock, who came from a line of Eton and London boat-builders, his dad’s uncle, William Pocock, was a London professional sculler and builder c.1840. He raced Harry Clasper on the Thames and afterward, invited Clasper to his shed to see the keel-less boat he was building. Supposedly, an article was written about this Pocock boat in a London newspaper. [If anyone has a lead about this article, I would appreciate any information.] The Pocock story goes that Clasper went back to Newcastle-On-Tyne and built a keel-less boat claiming it to be the first.

In any case, the first widely raced keel-less boat, The Five Brothers, was completed by Harry Clasper in 1844. It won at the Royal Thames Regatta on June 22, 1844 manned by the five Clasper brothers. Clasper built a new boat for the 1845 Thames Regatta called the Lord Ravensworth. This boat captured the World Championship on June 26 with four of the Claspers vs the London Coombes’ Crew and another London Crew containing Pocock.

In 1845 Searle took up the Clasper’s outrigger design he saw at the 1844 Thames Regatta and built an eight-oared outrigger.

Matt Taylor, England, took Clasper’s keel-less boat to the next level by applying a thin skin to the keel-less frame. In 1854 he constructed the Victoria that won the 1855 Stewards Cup at Henley and in 1856 he built a shell eight that won Henley’s Grand Challenge Cup. In 1856 the age of the racing shell began.

Following the developments in England, James McKay, a boat builder in New York, began building the sleek shells. Now, most improvements were developed in North America.

The general configuration for four-oared boats through the late 1860s included a coxswain to steer. At the Paris International Regatta in 1867, the Saint John, New Brunswick, coxless four arrived and defeated the other crews all rowing with coxswains. E.D. Brickwood states in 1876 that the Saint John four’s “victory was as much owing to their rowing without a coxswain”. Even earlier, in 1855, Harvard raced a coxed-eight and a second boat, a coxless-four vs. Yale’s two coxed-sixes. Harvard’s eight, with an adjusted time, defeated it’s coxless four by three seconds while Yale’s two coxed-sixes were third and fourth. It was not uncommon to have mixed boat types in a race, sometimes with handicaps and sometimes not.

Meanwhile, the English oarsmen at the International Regatta brought back the stories about this Paris coxless four. The next season, 1868, W.B. Woodgate had a coxless four built for the Henley Stewards’ Cup. He placed a temporary seat for a coxswain on the stern deck and, upon the starting command, the coxswain jumped overboard. Woodgate’s coxless four won the heat but was disqualified for the infraction, however, the result was the establishment of the coxless-four at Henley and in English waters.

Lightweight Paper Boats, c. 1868

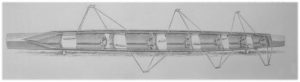

Paper boats were developed in the late 1860s and patented in June, 1868 by the Waters, Balch & Company in Troy, New York. They were a box manufacturer and devised a method of taking sheets of damp paper and forming them over a special mold, then drying and sealing the hull with a glue-resin type material. The U.S. Naval Academy was one of the first programs to purchase a Balch shell – a four-oared. From 1870 to about 1885 they were THE boat to have. The boats were widely used in all parts of North America and foreign deliveries were made as well.

The builder’s claim was that the hull shape could be exactly molded and built consistent with the designer’s intent. However, their life span was limited and they were difficult to repair. Once injured, they would absorb water and their high performance was compromised. In the late 1880s they began to lose favor and by 1895 they were mostly forgotten, but they were the rage in 1870s.

Here are some of the dimensions and weights of the paper boats in 1871: Single Shell Length – 30 ft. Width – 12 in. Weight – 30 lbs.

Double Sculls Length – 34 ft. Width – 14 in. Weight – 50 lbs.

Four-Oared Shell Length – 41 ft. Width – 18 in. Weight – 100 lbs.

Six-Oared Shell Length – 49 ft. Width – 19 in. Weight – 120 lbs.

Sliding-Seat

About the same time as Waters, Balch & Co. was developing their paper boat another important development was taking place in Boston.

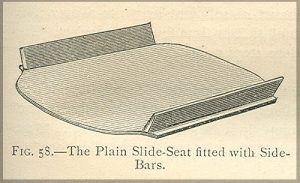

In November 1869 the Portland, Maine sculler, Walter Brown, raced William Sadler on the Tyne in Newcastle. While there he observed champion sculler, James Renforth, row. He noticed that Renforth slid on a highly polished fixed board using greased leather trousers. Brown returned and discussed sliding with boatbuilder William Ruddock. They designed a seat board that would slide. Ruddock built a cedar seat and at first used two cedar strips about 1 inch wide and 1/4 inch thick for the seat to slide on. Later he had two burnished metal strips made to replace the cedar strips.

Brown used the seat in a new boat built by Ruddock and raced in Boston’s City Regatta and won easily. He then loaned the shell to John McKeele to race Thomas Butler in Boston. The result was another victory for the sliding seat. Ruddock fashioned a patent model and Brown was awarded patent #107,439 .

Unfortunately, Walter Brown died unexpectedly on March 3, 1871 from contracting an illness. The patent fell to Brown’s wife but she wasn’t interested in it’s protection. Soon many other versions of the seat were developed.

J.C. Babcock of New York City who, as early as 1857 experimented with a sliding seat, in May of 1870 successfully fitted sliding seats to a Nassau Boat Club gig six. They raced at the Hudson Amateur Rowing Association regatta to test the seat’s merits. His conclusion was that on its first try the sliding-seats were a success.

J.C. Babcock described these seats in December, 1870 as “a wooden frame about ten inches square, covered with leather, and grooved at the edges to slide on two brass tracks fastened to the thwart, of sufficient length to allow a slide of from ten inches to a foot, though in rowing the proper length of slide is from four to six inches. The ways to be occasionally lubricated with lard, and I found no stops or fastenings necessary to keep the seat in position.” – Illustrated Catalogue and Oarsman’s Manual For 1871

The sliding seats were eagerly accepted by the racing community and everyone rushed to get their new sliding seat. Yale used slides in the H-Y Boat Race a little over one year after the Nassau trial race. Oxford and Cambridge used slides in the 1873 Boat Race. However, seats were sliding on greased rails. In November 1880 Octavius Laing Hicks, from Ontario, received a Canadian patent where wheels were attached to the seat, “to reduce friction… and to cause an easy motion”.

Numerous Improvements and Many Patents

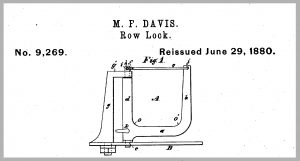

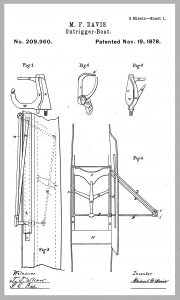

At this time, coming onto the professional sculling scene, was Michael F. Davis. He resided in Portland, Maine and The Spirit Of The Times in December 1879 described him “as the most noteworthy oarsman of modern times, an apothecary by profession, a gentleman by birth and education, and a professional oarsman by inclination.” From 1874 continuing through 1884, Davis revolutionized rowing equipment. I can’t think of anyone or any decade where so many new devices and new ideas sprung from one person’s mind.

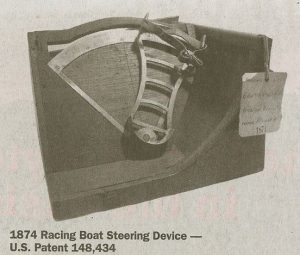

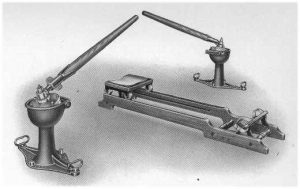

Davis was granted a series of patents (visit US Patents). They cover the swivel row-lock with numerous improvements, out-rigger connector castings so that steel tubing could be used instead of solid iron rod, the three-tube rigger instead of the four-tube type, reduced friction seats, sliding seat w/rigger, a modern type oar button, a roller bearing oar collar, steering foot-stretcher, a bow attachment called a “wind sail” to help compensate for cross-wind forces turning the boat. One of these is pictured on the 1881 Bowdoin College crew photo. His oar and scull patents will be discussed later with Oars & Sculls.

The swivel rowlock caught on quickly in North America, but was slower to find a following in England. It wasn’t until 1905, after the Belgians carried off a number of Henley pots while using swivels, did the British fully accept the device. Still, the fixed-pin rowlocks continued to be used in England where Leander Club won the Grand Challenge Cup in 1949 with fixed-pin rowlocks.

We can look back at this explosion in the development of rowing equipment and pick out the biggest breakthrough after the outrigger and shell construction. It was clearly the sliding seat. It changed the sport from one of fairly simple upper body power with static leg pressure to one of very complex power application. J.C. Babcock in his 1870 description is most intuitive in his evaluation of his new sliding seat: “the slide properly used is a decided advantage and gain of speed, and only objection to its use is its complication and almost impracticable requirement of skill and unison in a crew, rather than any positive defect in its mechanical theory.” M.F. Davis contributed many, many bits and pieces to the smooth operation of this new, complex rowing application. In a matter of several years, these two individuals transformed rowing from an early 19th century sport to what we know as a modern 20th century application.

I can’t think of any real significant changes in shells and hardware all the way through until 1972. In 1893 Cornell tried a boat made of aluminum, but it didn’t prove to be advantageous. From the 1880s to the 1960s, small improvements were made in seat design and wheel development. Boat framing was refined and shell designs were tweaked. But, no earth-shattering improvements were made.

Boat-builders were numerous. Each country would have local and regional builders with a few dominant national/international builders. Donoratico-Italy, Stampfli-Switzerland, Karlisch, Pirsch-Germany, Sims-Great Britain, and Pocock-USA were some of the nationally known builders prior to the 1970s.

George Pocock began building shells with his brother in Seattle in 1912. The Pococks were very open to try new materials and designs. The George Pocock Racing Shells company supplied most of the boats for the collegiate, school, club and Olympic teams in North America for two-thirds of the 20th c. Italian builder, Donoratico and Swiss builder, Stampfli, were two companies that penetrated the North American market in the 1960s.

Sliding Rigger, 1877-1983

The boat speed can be significantly improved by trading the sliding seat for a sliding rigger. This increases boat efficiency because body mass remains still on the fixed seat while the rigger/foot-stretcher unit slides. With body mass stationary, the boat doesn’t pitch bow to stern nearly as much, thus, less hull resistance is incurred.

The sliding-rigger dates back over 100 years before its c. 1982 re-introduction. In November 1876 William N. Blakeman Jr. patented “Sliding Row Locks” (US# 184,031) which shows a fixed seat and sliding riggers. And in April 1878 Michael Davis of Portland Maine applied for a patent for a sliding rigger/foot-board with fixed seat. This was only a few years after the sliding-seat became commonly used and is remarkable that someone was thinking well beyond the sliding seat. Davis’ reason has a bit of a twist. Seats still weren’t perfected and didn’t slide very smoothly. Davis was thinking that the excessive friction from a loaded (body weighted) moving seat could be eliminated by fixing the seat again and sliding the foot-board/outrigger components, “To avoid this great amount of friction… is the purpose of this part of my invention. The means used to accomplish this result are a sliding foot-board and outriggers.”

It is reported that this sliding-rigger concept was tried by Walter Hoover (USA) in the 1920s. The mechanism was used in 1954 by C.E. Poynter of Bedford (UK). The September 25, 1954 Illustrated London News described the invention in a double-scull. The concept surfaced again in 1960 when Nick Smith (AUS) fitted a practice boat with a sliding-rigger system.

Around 1981 Empacher Bootswerft (GER) perfected the device using modern materials and hardware. Germany’s outstanding sculler, P. Kolbe, won the FISA World Championship in it and everyone rushed to get a new boat with the mechanism. At the 1982 World Championships 1st through 5th place used sliding-rigger boats while the only sliding-seat boat in the finals placed 6th.

In August of 1983, FISA banned the use of the sliding-rigger beginning January 1, 1984 because it was thought to be more costly than sliding-seat boats. This may or may not have been true. Nick Smith in his book, Rowing and Sculling, makes a good point about how the sliding-rigger could be removed after arriving at the float just like you remove the sculls. This makes carrying the boat easier and many more boats could be stored in the same space as conventional boats.

I also think that manufacturing costs of the sliding-rigger would diminish as the materials technology improved. Today we see the cost effective wing-rigger and this technology is easily adaptable to the sliding-rigger mechanics. Who knows, maybe the sliding-rigger will surface once again.

Composite Boats, c. 1972

In 1972, in preparation for the Munich Olympics, the German federation supported an equipment development program. Empacher Bootswerft was one of the recipients of this financial support and experimented with the newest materials – glass/carbon fiber/honeycomb and epoxy resins. The result was a couple of state-of-the-art shells competing in Munich. From this point on, shells of fiber reinforced plastics became more prevalent. In just 2-3 years a majority of boats racing at the World Rowing Championships were made of these high performance materials and most were built by Empacher.

The traditional wooden boat builders had to either transform themselves from craftsmen to materials engineers or close their doors. Many didn’t make the transition. Besides Empacher, new company names appeared: Carbocraft (England), Schoenbrod (USA), Van Dusen (USA), Hudson (Canada), Carbocraft-USA now known as Vespoli USA. Some builders did make the transition: Pocock (USA), Stampfli (Switzerland), Kaschper (Canada) to name a few.

The result of this transformation from wood to carbon fiber/honeycomb/epoxy is that boats weigh less. Wooden eights in the 1950s were 300 pounds while eights in 2000 are a little over 200 pounds. They don’t glow with the same beauty, heart and soul as the wooden craft, but they’re much stiffer, stronger, more durable, can be more easily repaired and require less maintenance than their predecessors.

Oars and Sculls

It seems that oar and scull developments have been a little more gradual. The early oars (17th c.) were straight with a very long flattened surface and square looms. Then some time (18th c.) they became a little more contoured with a curve to the blade, but still a long slender blade. Into the 19th and 20th c. many blade shapes were tried. Some had a short life while others were widely accepted.

Many materials have been used to make oars: wood (sitka spruce), aluminum and composite materials (fiberglass, carbon fiber, Kevlar™ fiber). The real challenge to make oars using composite materials in the 1970s was to make an oar that would perform, be durable, and be cost effective.

In 1972 a British company, Guest, Keen and Nettlefolds produced a set of carbon reinforced oars for the ARA for the Bristish Olympic team, however, they were very costly. In 1977 the Dreissigacker brothers, Dick and Pete, founded Concept2 in Vermont to manufacture carbon fiber oars. They devised a production method and developed a composite oar that became the choice of all North America and much of the rest of the world market. Other manufacturers made carbon oars, but Concept2 satisfied all three of the parameters the best and earliest.

In the Fall of 1991 the Dreissigackers experimented with a new blade design. It was soon called the hatchet blade because of its cleaver like shape. It’s acceptance was immediate and the first crews to use them were successful on the race courses. FISA entertained a ban on the oars because they felt that all the competitors at the quickly approaching Olympic Games would be unable to purchase the oars in time to compete in Banyoles. Concept2 assured the governing body that all orders would be produced on time to meet demand. Their word was accepted and they met their orders. Today many manufacturers are producing the hatchet blades and some design variations exist. The hatchet blade prevails and the symmetrical Macon blade can’t be found racing anywhere.

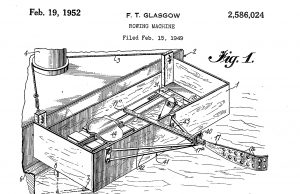

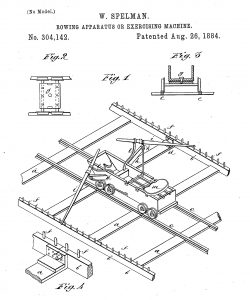

Rowing Machines

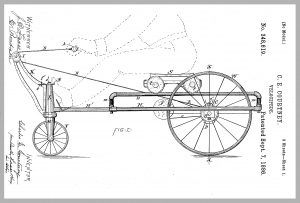

Rowing machines have been in use since at least the mid-19th century. There are advertisements and patents dating back to that era. The patent below is an improved rowing machine patented in 1871 by W.B. Curtis. William Curtis was one of the most active people in the rowing community. He, along with two others, founded the New York Athletic Club. He also was the person who called for a meeting of all amateur rowing clubs for the purpose of forming the N.A.A.O.

The Narragansett Machine Company in Providence, RI produced hydraulic rowing machines from about 1900 all the way through the beginning of the 1960s. The Narragansetts can be seen in numerous old photos of college crews training indoors. Some photos show them onboard ships transporting crews across the Atlantic for Henley and the Olympics. If you look closely the next time you watch Titanic, the movie, you’ll spot a couple of Narragansetts onboard in one scene. These machines were the foundation of winter training along with indoor tanks for the major college programs.

In the early 1960s an Australian company built a machine called an “ergometer”; a machine to measure work capacity. They were very large steel devices with flywheels and leather straps applying resistance. Two were purchased by Harvard and then two more were bought by the Naval Academy. These machines were used to test the output of some of the 1968 Olympic team hopefuls and were subsequently used to do the first aerobic testing of oarsmen by Dr. F. Hagerman – 1968-1970. They were a bit sensitive to humidity and temperature, so scores couldn’t be universally compared.

In 1970 Gamut Engineering in California developed an effective less sensitive rowing machine. It became the foundation of winter training and testing of college and national team rowers through all of the 1970s. Today, they’re still utilized in some rowing programs.

From Norway came the Gjessing-Nilson ergometer using a friction brake mechanism. It became the internationally accepted testing standard for a while.

In 1981 the brothers, Dick and Peter Dreissigacker, designed and produced a much simpler and cost efficient rowing machine called the Concept2 Indoor Rower. The first model used an open bicycle wheel fitted with plastic paddles to create air resistance. After design improvements, the machines today are shipped world-wide with thousands in health and fitness clubs everywhere. Just as Henry Ford produced cars efficiently, economically and for the greater public use, the Dreissigacker brothers have done the same with their rowing machines for the rowing, health club and home markets. The design has gone through continuous improvements and is one of the most dependable and cost effective exercise machines developed since the bicycle. It is certainly a major factor in the explosion of interest in rowing as an exercise with the general public.

What started in 1982 as a fun event to add some humor during the college winter training period, the CRASH-B Sprints or more formally called the World Indoor Rowing Championships, draws competitors from all over the world. The bicycle wheel model (Model A) was used for the first few years with a mechanical speedometer/odometer testing the competitors for a 5 mile duration. The Model B was the next generation with a wire enclosed, cast alloy flywheel and electronic monitor outputting metric distances. The CRASH-B Sprints tested the competitors at a distance of 2500 meters. Concept2 made more improvements and the Model C was introduced. Eventually the CRASH-B Sprints settled on 2000 meters as the race distance.

Other Equipment Ideas

See many more rowing patents at Resources / Patents

Boating Names & Terms

Oar – An oar is an implement where only one is used per person. The racing oar is approximately 12 1/2 feet long and the rower places both hands on the handle. A sweep (12-14 feet) is a longer oar used more in open water boats.

Coxed-Pair – Two rowers/two-oared boat containing a coxswain – sometimes it is informally referred to as a pair/with (coxswain) or pair/w or 2+

Coxless-Pair – Two rowers/two-oared boat without a coxswain – sometimes it is informally referred to as a pair/without (coxswain) or pair/wo or straight-pair or 2-

Coxed-Four – Four rowers/four-oared boat containing a coxswain – sometimes it is informally referred to as a four/with (coxswain) or four/w or 4+

Coxless-Four – Four rowers/four-oared boat without coxswain – sometimes it is informally referred to as a four/without (coxswain) or four/wo or straight-four or 4-

Eight – Eight rowers/eight-oared boat containing a coxswain – 8

Sculls – A pair of smaller oars used by one person. Each scull is approximately 10 feet long and the sculler holds a handle in each hand.

Single-Sculls – The name for the boat sculled by one person – sometimes referred to as a single or 1x

Double-Sculls – The name for the boat sculled by two people – sometimes referred to as a double or 2x

Quadruple-Sculls – The name for the boat sculled by four people and usually doesn’t contain a coxswain – sometimes referred to as a quad or 4x

Octopede – The name for the boat sculled by eight people and containing a coxswain

Wherry – This is the name used for the every day work boat used by the Thames River watermen. The term goes back to the first descriptions of rowing on the Thames and can be seen on the title page and rowing description in Walker’s Manly Exercises-1834.

Cutter – A heavily built rowing boat usually manned by eight rowers and coxswain and sometimes containing a station in the bow for a passenger. Before the days of steam launches, cutters would row along following a race with the umpire in the passenger station.

Barge – In the 20th century, it is a heavily built and wide-beamed rowing boat for teaching rowing and/or room to carry gear for an excursion. Also, in 15th-19th century England, it is a large elaborate ceremonial ship to transport dignitaries on the Thames. Also, in 19th and early 20th century England, this type of large elaborate ship was used as a boathouse and club-room for the college crews at Oxford and Cambridge and others clubs.

Tub (English) – A wide beamed training boat usually a pair with ample room for a coach-coxswain.

Wager Boat and Best Boat (English) – There were various terms used in England referring to the newest, most race-able boat. These were the boats raced when valuable prizes were on the line.

Ran-Dan (English) – an unusual boat of three people configured as two rowers and one sculler.